There’s a theory that when you see a bear in the woods, and you start to run away, and your heart is racing and you start to shit your pants, your conscious mind isn’t doing any of that.

That seems obvious. Most of us know that’s not how you’re supposed to react to a bear. Shitting your pants is usually not a conscious, measured decision (although to be fair, I’d be less likely to try to eat someone if they had dookie drawers).

In that situation, that’s your amygdala, or your instinctual mind at the controls (as it often is). The amygdala has caused that entire reaction before your conscious mind even knows what is happening. You feel afraid, but not because you saw the bear–not at first. The first and primary reason you’re consciously afraid is that your fear reactions have instinctively gone haywire and your mind is going, “Well I’m running, my heart is about to explode, and I’m going to have to throw these pants out. I must be afraid.”

It’s only right after that reaction that your conscious mind catches up and registers the thought of, “Oh shit! A bear! Aren’t I supposed to not run in this situation? Aw, balls!”

All of this is to drive home the most important and repeated point of Amy Alkon’s book, Unfuckology: More often than not, our conscious mind doesn’t decide what to do. It responds to what our unconscious mind is already doing. Therefore, our emotions and future actions are most predominantly influenced by one thing: our current actions. The main reason you’re reaching for that jar of queso is because, well, you’ve always reached for that jar of queso.

So if you’re wondering, that is why you look like that.

This begets two more important points:

“Recognizing that the body is often a part of cognition–of thinking–is essential to the formation of the new you.”

“By repeatedly changing your behaviors, you embed the behaviors and their companion emotions into your brain.”

Fix Your Actions, and The Rest Will Follow

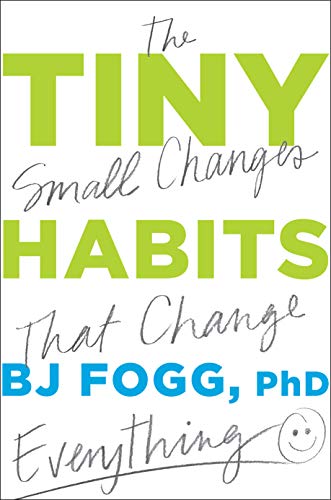

So if we can change our habits, and the way we exist on the exterior, we can change the thoughts and feelings we have about ourselves, and the actions we automatically do in response to those habitual actions.

We can change ourselves internally by changing our external actions.

The simplest example of this is in smiling. People who smile more–regardless of whether they actually have reasons to be smiling–are tested as being happier. It seems incredibly stupid that you can just trick your brain like that, but you can’t really argue with the research.

The book even cites a study wherein participants got botox that prevented them from frowning, and the results were that it lowered their depression. To be fair, it’s not clear if that was because they couldn’t frown, or because they got rid of those God damn wrinkles around their lips, and their partners therefore started liking them more, but that could really go either way.

Trick Your Stupid Brain

This all means that the central thesis of the book is that your conscious brain is an idiot and it can be tricked. When you do this, you’re faking throwing a tennis ball towards being less of a shitty person, and your conscious brain is a dog running after it like a dipshit.

In other words, if you start to walk around like you’re confident, the emotional brain will register that as confidence, and your conscious thinking brain will then just be confident.

If you put your dumb body in a gym to work out every day, you’ll start to automatically register going to the gym as a thing you do, and eventually, you can reach your goal of being some muscly weirdo who sells protein powder on Instagram.

If you start to tell yourself you’re enjoying celery as you eat celery, eventually your conscious brain will be like, “Oh fucking cool! Celery!”

The point as it pertains to our life in general, is that we’re naturally predisposed to doubt ourselves, to protect ourselves, and to be shitty versions of ourselves who don’t even scratch our potential. But we can trick our brain to overcome sucking in all of these ways.

You Are Not Your Feelings

Another really important point in the book is that you are not your feelings. Feelings are going to happen to you, and they’re going to control you to some extent, but you have some say in that. You can take note of the feelings, say “fuck that shit,” then let them pass, and do something else.

So when that bear approaches you in the woods, if you’re someone who habitually has control of their feelings, you can stop yourself from running, screaming, and maybe even shitting your pants. And you can….I don’t know, throw a stick for it to fetch? I don’t know what you’re actually supposed to do in that situation. Google that. That’s not the point.

The point is that when someone is an asshole to you, and you want to kick them in the nuts, you can stop yourself, let your emotions pass, look at them calmly, and say, what you find to be the most effective rational response (I personally am a big fan of “I know you are, but what am I?”).

The goal isn’t to not feel your feelings. The goal is to take as much control as you can of what you do when the feelings come up.

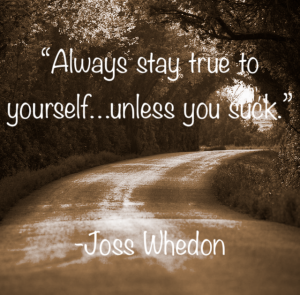

Don’t “Do You”

Perhaps the best, most important section of the book is fighting against the idea of being yourself.

This isn’t a very popular notion in the feel goodery sect of the self help genre. Most of self-help hypocritically boils down to, “You’re awesome and amazing! Here is how to…uhh…improve everything about you!”

The argument this book makes (and I often make) is essentially the famous Joss Whedon quote:

Given the rest of the book, the main argument here is that if you have parts of you that aren’t working for you, or the world, you shouldn’t stick to those in the name of some kind of misplaced individual integrity. You shouldn’t keep scrolling through the timeline instead of doing anything productive, or eating deep fried garbage, or leering at high school girls just because, “This is WHO I AM, MOM!”

The book argues that you should change you. Look in the mirror, and be like, “Oh these parts of me suck. I’m going to start doing different things so that they suck less.”

Weird Diversions

The over all concepts of the book are really solid, and useful, and come highly recommended.

Some of the specifics of the book lose me. Alkon has large swaths of the book where she shows a kind of bizarre loyalty to two kind of shitty ideas: 1) Making people like you is really important and should be a priority, and 2) Gender roles.

The loyalty is bizarre because after an entire book where the primary point is, “Yes we’re biologically predisposed to x, y, and z, but we can recondition ourselves through habits, action, and rituals to be different both externally and internally,” she instead really leans into the ideas of, “You should care about what others think of you because you naturally do, and men are meant to chase women, and there’s nothing we can do about that, and any other way is bullshit.”

These things may both be built into us, but so is our shitty anxiety, and lack of productivity, and tendency to deep-throat mozzarella sticks, and those can all be changed. So why can’t we also change our reliance on outside approval? Why can’t gender roles be determined on a person to person basis, and in some cases, universally thrown in the dumpster?

This is not only inconsistent, but also, in my opinion, bad. Besides the shitty results of some natural genders roles, training yourself to be less reliant on outside approval is not only doable, but very positive. Leaning into your urge to make others like you will just cause you to spend a whole bunch of social time guessing as to what others will like while you spend less time focusing on cultivating what you like about you.

To go against this is to settle on our current dumbass evolutionary step where we’re like, “Oh I really hope her parents like my witty quips while we play board games!” which, good God, what a loser you are.

But for the most part, the book is fascinating, well-researched, and worth reading. It can change the way you view your behavior and psychology in the future, maybe even help you unfuck yourself, and control how you handle a bear attack.